First book I've sat down and read in a long while. I've been listening to a lot of Horus Heresy era Warhammer audiobooks too. It's pretty good if you like Warhammer40k but it's basic bitch grim dark sci-fi war stuff.

Good one. Thanks!GloryofGreece wrote: Tue May 21, 2019 10:49 am "Call of Cthulhu": Lovecraft, and why Horror is Reactionary"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JxWPVlxoSn0

Yeah? I read some reviews and it sounded like Stephenson in "unreadable" mode. He's basically become "editor proof", bad for a writer. He, GRRM, Rowling & King all are free to run off the rails. It's been a long time since I thought a NS book was unreservedly great, Seveneves was pretty good, but as usual the last 3rd was weird as fuck, same as even as far back as Diamond Age.California wrote: Tue Jun 18, 2019 6:09 am Another great Stephenson so far

It is set in the Shaftoe-Waterhouse world...

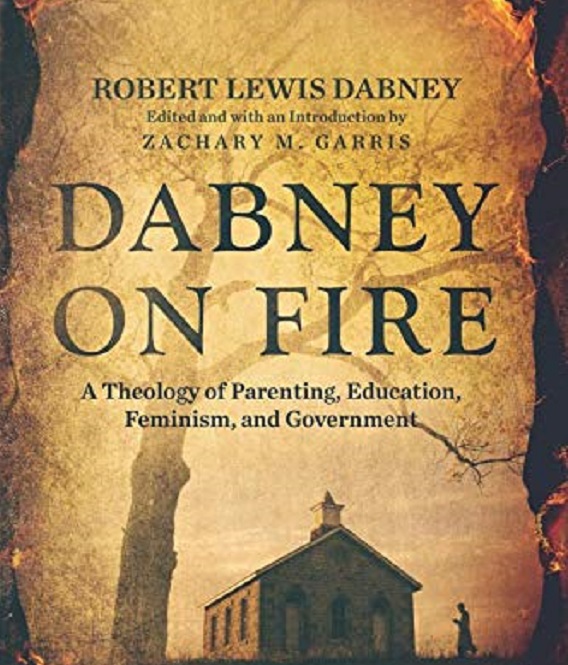

During his lifetime, Southern theologian and writer Robert Lewis Dabney was most notably known for his 1866 biography of General “Stonewall” Jackson (The Life and Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. Thomas J. Jackson) and for his post-war apologia for the Southern cause, A Defense Of Virginia, And Through Her, Of The South, In Recent And Pending Contests Against The Sectional Party (1867). But his renown as a theologian and philosopher were also well-established. In addition to serving as chief of staff for Second Corps under Stonewall Jackson, and being a Professor of Systematic Theology at Union Seminary in Virginia (until 1883), he also served as Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy at the newly-founded University of Texas until his retirement in 1894. His volumes Practical Philosophy and Sensualistic Philosophy of the Nineteenth Century and his membership in the Royal Philosophical Society of Great Britain attest to his expertise and international fame.

. . .

More so, state-run education sought to impose an unnatural equality on all. “Providence, social laws, and parental virtues and efforts, do inevitably legislate in favor of some classes of boys,” he declared. “If the State undertakes to countervail that legislation of nature by leveling action, the attempt is wicked, mischievous, and futile.” Indeed, Dabney questioned “whether the use merely of letters is not education, but only one means of education, and not the only means.” True education involved more than simply the use of letters. Most citizens had traditionally found education through their various professions, a training of the “moral virtues by the fidelity and endurance” with which they earned their livelihood. The laboring man “ennobles his taste and sentiments by looking up to the superior who employs him. If to these influences you add the awakening, elevating, expanding force of Christian principles, you have given the laborer a true education…a hundred fold more true, more suitable, more useful, than the communication of certain literary arts, which he will almost necessarily disuse.”

Almost alone among writers of the late nineteenth century, Dabney saw the distinct danger of the new public school system being used by “demagogues, who are in power for a time, in the interests of their faction.” And his most serious indictment of public education has become a question that has only become more critical since then: what happens to religious instruction if the state takes over the teaching of children? Given the status of post-war relations between church and state and changing constitutional interpretations, the state could not endorse one religious belief over another. State-sponsored education would become secularized. But if education were not Christian, then it would inevitably become anti-Christian. “He that is not with his God is against Him,” Dabney repeated. Could education really be education if it educated “the mind without purifying the heart?” Dabney answered: “There can be no true education without moral culture, and no true moral culture without Christianity.”