I think you already see in this thread some of the philosophical reasoning for why that would be: It's of course not that there is some sort of objective measure of "importance", it's that because of the societal mentality for most of history, lower classes simply did not consider themselves worthy of the same sort of attention. Also, for most of medieval and ancient eastern history, the focus on history has been dynastic history and genealogy. For most of history, there were no "historians" in the same way your professor's a historian.Sparrow941 wrote:

Im not talking about today’s elites. I was answering the question “Why is there no peasants writing about history throughout history?” The things required to write histories (reading documents, interviewing people, training in critical thinking, not being exhausted because you just fucking tilled fields for 16 hours) were not available.

Geneaology and history was used to legitimize land claims, power structures and status. It took more than the printing press to be invented for people to suddenly give a damn about their personal history or geneaology. It took a sense of individuality, a sense that it wasn't just "The Great Man", the elites, who created history. As you no doubt know given your line of study, the idea that history is something that "happens to" those lower on the totem pole, that history is no more than the study of the trickle down effect of whatever decisions made by emperors, kings, nobles, generals and politicians is not one that is common in the study of history anymore.

From the more practical perspective, which is the main reason peasants didn't write volumes of history from their perspective, or about their own lives. You already point out their work hours, so I don't know why you'd ask that? When would they ever find the time? If they found the time, they wouldn't be peasants, since someone else would have to do their jobs, and they'd be the new peasants. Their "place" in the power structure was set, fixed, divinely mandated, considered natural and eternal, same as it was for the different layers of the nobility, clergy, merchant classes and serfs (and slaves).

The idea of individuality, the idea that you had value as an individual, that your place in society was not permanent, caste-like, a natural order, fundamentally changed that structure. Because one of the classes of people who, while not on the bottom rung of society, had been considered lower class and engaged in non-prestigeous work (merchant/trading) suddenly started to gain economic power, then they to send their sons off to study. Those sons wrote works of philsophy that would lead to the Enlightenment, to the notion that it should be the middle class/merchant classes, those who actually produce worth rather than simply collect tithes or taxes simply by "virtue" of station and blood rather than industry and merit.

This is why your history professor was right to call into question your notion that the elites, and those who write history, are one and the same. StA is closer to the truth here, with one elite in conflict with another, the power-as-blood elites eventually losing in most countries to the power-from-merit and industry elites and their way of seeing history.

However, you phrase a question like this:

They aren't, really. Historical sources are more than just text. A historical source is also mosaics, church murals, it is archaeological objects, it is anthropological data from the dead of the past. From all of these, you can gain insight into the life of those who a king's chronicler may not speak so much about.“Why are most historical sources about political dealings, diplomacy and military engagements.?”

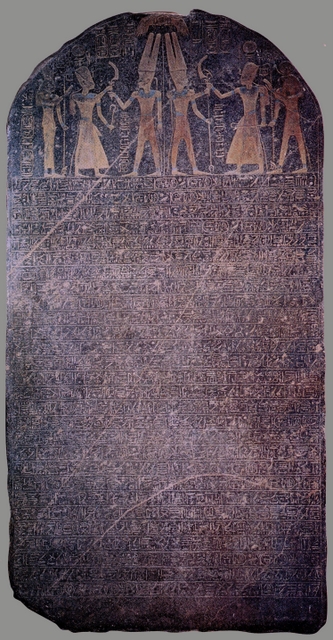

But even in the texts, you can find sources depicting the lives of peasants. Reading medieval law texts, convictions, late medieval taxation papers. All of that, while written by whichever local judge or official appointed that duty, isn't the peasants writing about themselves, but it is a source on their lives, and thus can be useable source for any present day historian who would want to write about what sort of lives they lead. As your will know what makes a source a source is entirely relative to what you are looking for. If you are researching 14th century steel-making techniques, an 14th cent AD Aztec mural depicting a god creating the world or a 14th cent BC Mesopotamian stelea announcing that so and so ruler is so and so magnificant, is not a source.

The idea that the preservation of history is dependent solely on preservation of the original medium sort of ignores that the way we preserved most ancient books and texts from ancient times to modern times, is through copying them. Also, historians today...and this has been the case for the discipline for over a century, don't concern themselves only with "Great Events" as you call them. Knowing only how the top of any historical society lived, quite simply doesn't give you an accurate picture of that historical society. That is naturally true for present day societies as well.GCF wrote:Even CDs and hard drives won't last more than a few decades (assuming that we could still use them). It requires an extremely durable medium, and a near-perfect storage that won't be tampered with. That sort of thing isn't done for any less than Great Events, unless there's a fluky thing like the Dead Sea Scrolls that get forgotten about for centuries.

But about the worry that because you soon won't be able to read CD's, all of the data stored on them will be gone forever, or that what's being preserved is only about "Great People" and "Great Events":

http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/about/